Dr. Martin Soder and Dr. Imogen Dalmann

Dr. Martin Soder and Dr. Imogen Dalmann are medical practitioners in Berlin, Germany. They are also Yoga teachers and were students of Śrī TKV Desickachar. They also published a Yoga journal in German called “Viveka.” This article was originally published in KYM Darśanam, August 1994.

This article presents the modern view on the mechanics of breathing in the medical profession. This is in conformity with how Yoga understands this process and validates these techniques.

Breathing occupies the central place in Yoga practice. It is the link to our mind, the indicator of our situation, and the key to healing and well-being. The breathing pattern in Āsana practice requires the understanding of the natural relationship between breath and body movement. Given its overriding importance, the correct technique of breathing is the first thing that is taught to a student. Movements and postures are taught that will facilitate the right use of the spine, chest and abdomen. This is done on the basis of the mechanics of the movements involved, as understood by Yoga.

The question of the optimal conditions for a strong and harmonious breathing movement has been of interest to anatomists and physiologists through several decades. More and more precise measuring procedures have helped explore the course of the breathing movement and the forces involved in every detail. The research has not yet come to an end and there are still questions to be answered. Here is a short summary of the proven facts:

- Inhalation and exhalation are complex movements that combine two mechanisms of breathing, the movement of the diaphragm and the movement of the chest cavity.

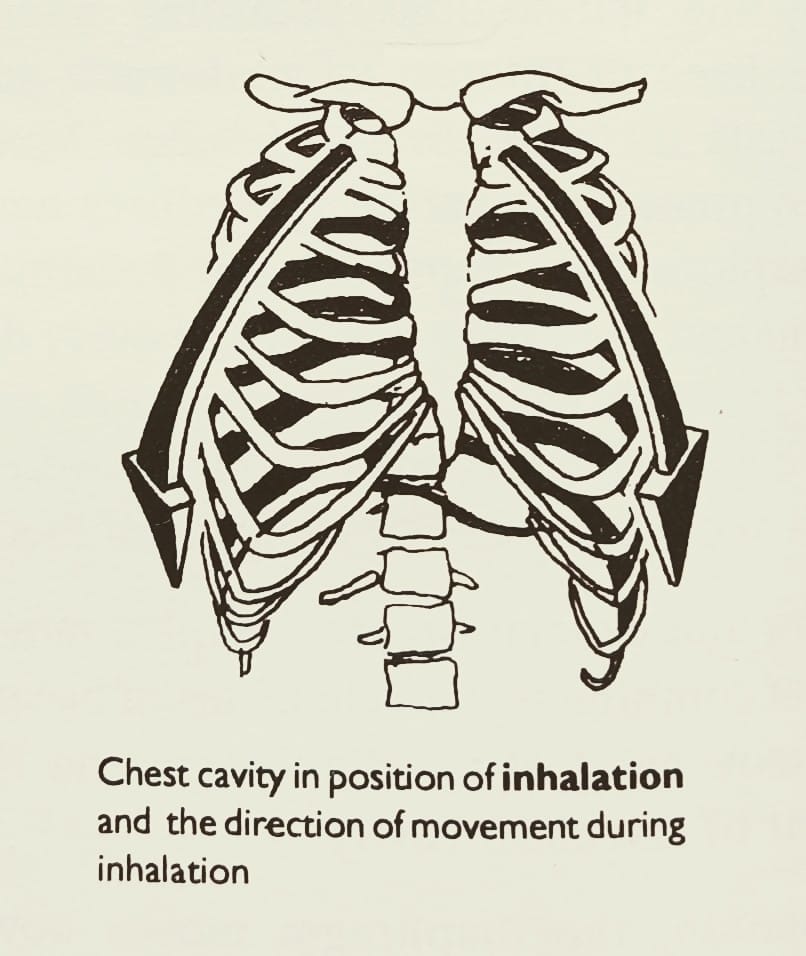

- On Inhalation, the diaphragm moves down and the chest expands.

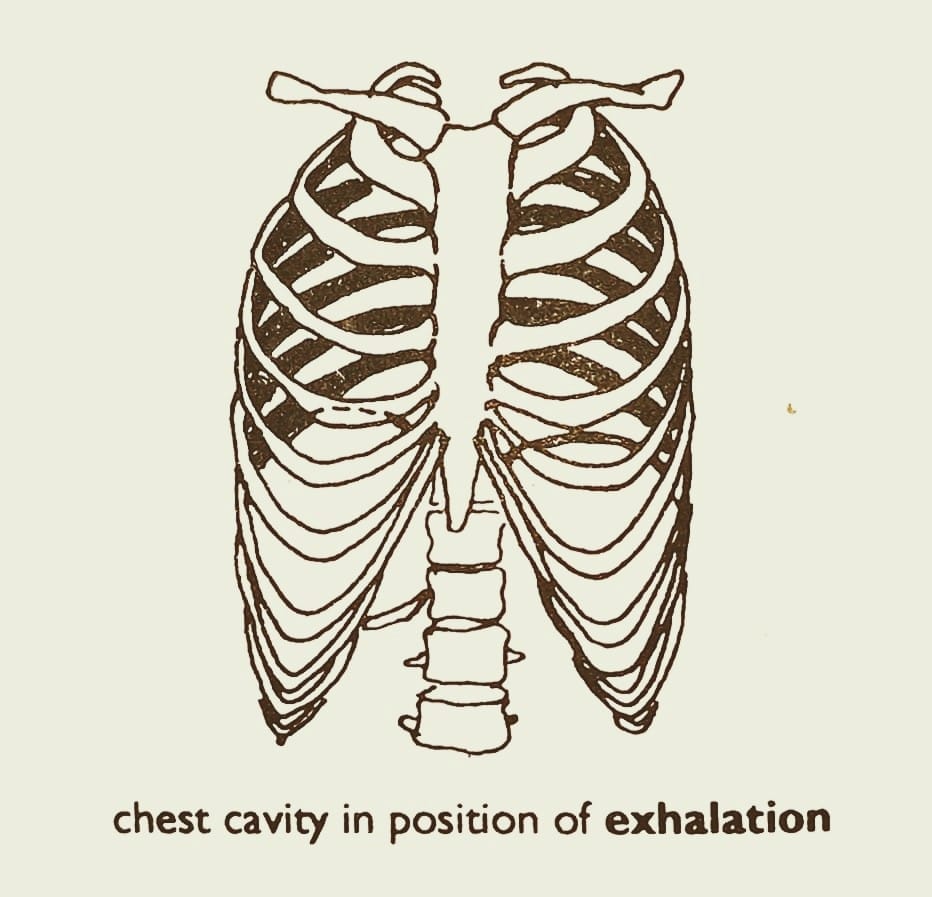

- On exhalation, the diaphragm moves up and the chest contracts.

- When the breathing is calm and shallow, almost the entire breathing work is done by the diaphragm. Its movement can be observed as the lifting and lowering of the abdominal wall.

- When the breathing is deeper, it becomes complex. The thoracic breathing comes into action in addition to the diaphragmatic breathing.

- So, deep inhalation must show significant lifting of the ribs, with the lower frame of the thorax moving upwards and extending to all sides. This is in addition to the downward movement of the diaphragm.

The process of inhalation and movement of the spine is intimately connected. What was observed and published in an orthopedic journal by M. Jansen, 80 years ago, has now been proven even more precisely by measuring the electrical excitation impulses of the muscles. When a person breathes in, the erector spinae muscle contracts with the effect that the spine straightens. In Jansen’s opinion, the erector spinae muscle plays a vital role in each inhalation. “With the breathing going in and out, the spine is rhythmically moved. With inhalation, the spine is straightened. With exhalation, it is relaxed. This is done involuntarily. The involuntary (reflex) movement of the spine, however can be influenced by the voluntary muscular activity, i.e., it can be either supported and strengthened or irritated. This connection can not only be seen as a mechanical process but it is intertwined with and initiated by the nervous system. The straightening of the spine makes the expansion of the thorax volume possible.” (Quotation from the first volume of Penningoff Anatomy, 1985, Reinhard Putz)

Inhalation is always accompanied by the straightening of the thoracic spine. Almost simultaneous with the activation of the diaphragm occurs the contraction of both the erector spinae muscle and the scalenus muscles that lift up the upper ribs. This happens even if the person is breathing calmly.

During inhalation, the movement of the ribs begins with the upper front part of the thorax and spreads downwards to the lower sides. The air moves in the same direction, from the top downwards. The outward expansion is due to the lifting of the ribs and straightening of the upper back. The downward spread of the movement is due to the lowering of the diaphragm.

The three important processes during inhalation are:

- The diaphragm starts moving down at the beginning of the inhalation but comes to its most intense movement at the end. The moment of the diaphragm itself cannot be seen, but its effects can be observed, i.e. when moving downwards the diaphragm presses the abdominal organs towards the abdominal wall which thus budges outside.

- Inhalation always means expansion of the thorax and its lifting – from the top downwards. The movement of the thorax which starts immediately after the first activation of the diaphragm can be observed as the beginning of the inhalation; the movement of the abdominal wall is seen afterwards.

- Inhalation is always accompanied by the straightening of the upper back.

The combination of the lifting of the ribs and the straightening of the spine is made possible through the spinocostal muscular loops which connect the spine with the ribs. They build a ‘fixpoint’ at the spine for the external intercostal muscles. Through these, the contraction of the external intercostal muscles is transmitted to the spine.

The support for the thoracic movement on inhalation is provided by the straightening of the upper back. When the muscle connecting the rib to the spine contracts, either the rib can rise or the spine can bend towards the rib. The normal movement, i.e. the rising of the rib, is made possible by the contraction of the muscle on the opposite side. This keeps the spine erect and provides the support for the rise of the rib.

It is interesting to see that, with an infant, even deep breathing is predominantly done by the diaphragm. Only when the child starts walking upright, using the spine as an aid to do so, does the breathing process become an interaction between the movement of the diaphragm and the thorax as well as of the breathing movement and the spinal movement. Only the upright position makes the complex expansion during inhalation possible.

Let us now take a look at exhalation. It is much simpler and mainly passive. The diaphragm relaxes and moves upwards, the abdomen goes in, the thorax goes down and the back bends forward slightly.

In order to learn about deeper exhalation, we can look at what happens when a person sneezes or coughs. There is an intense inward movement of the abdominal wall. The pressure that arises on the inner organs is transmitted to the diaphragm and supports its upward movement. We can use this mechanism to reach a deep exhalation by activating the muscles of the abdominal wall. If the activation of the muscles starts in the lower abdomen, the exhalation movement becomes most efficient and results in the automatic lowering of the thorax.

The movement of the abdominal walls towards the spine causes straightening of the lower spine which means, in a way, a compensation of the lordosis of the lower back. Inhalation straightens the upper back and exhalation straightens the lower back. At the same time, active exhalation moves the inner organs and tones the abdominal muscles.

A short summary of what modern anatomy and physiology have to say about the breathing movement:

- Inhalation and exhalation are an interaction of the movement of the diaphragm and of the thorax.

- Deep and complete inhalation:

- It lifts the thorax. The movement begins from the top ribs and proceeds downwards to the lower ribs.

- The process straightens the upper spine in the same manner.

- Moves the diaphragm downwards at the same time.

- Deep and complete exhalation can be reached by active contraction of the muscles of the abdominal wall beginning with the lower abdomen and this moves the diaphragm upwards.

- In order to have a good breathing movement, we need an upright spine and flexibility in the upper and lower back.

It is important to distinguish between certain breathing techniques on one hand and the physiological breathing process based on anatomical functions on the other.

As a technique, almost everything is possible. In some Japanese monasteries, a kind of paradox breathing is taught where during inhalation, the abdomen is pulled in and on exhalation it is pushed out. There are breathing therapists who advise their students to bend the upper back on inhalation. In Nāḍīśuddhi Prāṇāyāma, the flow of breath is manipulated while fingers being placed on the nostrils. Any breathing technique can be justified if it can be shown to serve a particular purpose and is taught with an understanding of the factors involved.

These results of modern research on the physiological process of breathing, thus validate the traditional Yoga techniques, where the spine, abdomen and chest are focused on to aid the breathing process.

To improve the quality of our breathing and through that, the quality of our life, we can work towards: an erect spine, free movement of the diaphragm, good contraction of the abdomen and straightening of the lower back. Inhalation should lead to a good exhalation and vice versa.

(The above material is taken from the article ‘Bewgter Atem – So sicht’s die Wissenschaft’ which appears in the journal Viveka Nr 1. We are grateful to T. K. Raman and Dr. Beatrice Muller for translating the above article to English).